Governmental institutions are challenged to use design and open design as a strategic tool. Bert Mulder addresses issues of participation and quality, and suggests how a government could develop a system that would include information, tools, methods and a set of values to reap the benefits of open design for citizen involvement.

Open design for government is a challenge. Not only is open design itself a relatively recent concept, but design and government generally do not interact easily. We do not often talk about governments designing things; we say that governments institute policy and procedures, develop urban planning and create services. Even in a recent Dutch initiative with the grand name of The Hague, Design and Government the tagline reads ‘design for public space, architecture and visual communication’. When design for government is discussed at all, design is mostly seen as functional.

But design will become an increasingly necessary and strategic tool for government at all levels. That is why exploring the relationship between open design and government is not only interesting, but also timely and necessary.

Today’s society requires us not only to create a wider range of diverse solutions, but also to do so faster and better.

Exploring the possibilities of open design for government requires delicacy. Much of open design thinking seems to be in the ‘hype’ phase of Gartner’s hype cycle, where arguments for and against reflect hopes and expectations rather than reality, simply because there is little or no experience on which to base tangible forecasts. This article takes a somewhat analytical approach, outlining several qualities of open design and government and identifying potential challenges. It describes a plan and proposes developments that would stimulate open design in the public sector. Essentially, this article tries to envision what open design would be like as a structural and strategic tool for government.

The Importance of Design

The first reason to consider open design for government is the increasing importance of design across the board. This increase is occurring because our increasingly complex society requires more design. TREND Where supermarkets in the 1960s stocked 1000 products, today’s supermarkets carry between 20,000 and 40,000 items. All these products need to be created, produced, marketed, bought and used. This process is why design has grown from ‘nice to have’ to ‘need to have’: we need to create more products and services to sustain our society, and to present them in a way that is meaningful to us.

But design is also becoming more important for another reason. Today’s society requires us not only to create a wider range of diverse solutions, but also to do so faster and better. New challenges require fundamentally new solutions; simply extrapolating the past will no longer suffice. And because solutions will have to survive into a future different from today, the ability to design well becomes more important. We need to shape society with the future in mind, REVOLUTION not relying on a past that increasingly has little bearing on the problems we face today; we need to realize better and more sustainable solutions using imagination, innovation and our talent for creativity and creation.

Why Government is Involved in Design

Future-driven thinking is what makes design fundamentally important for government. To face the challenges that the future will hold, the government needs to develop and integrate design competencies into its processes. Analysis and simple extrapolation governed by political processes will have to give way to imagination and more original creation, buildings more sustainable solutions. The development of social innovation serves as an example: design professionals are creating novel solutions in social contexts. SOCIAL DESIGN This approach involves a more strategic use of design by the government than the simply functional use of design in public space, architecture and visual communication.

A second reason why design capability becomes essential for government is the new complexity of the networked society: government policies and services are increasingly developed in networks that link many different partners. The complexity of a context involving many different stakeholders and regulatory frameworks makes it essential to have a central concept to bind it all together. These considerations also mean that any development in the design field will potentially have relevant applications in the public sector. Clearly, the development of open design for government purposes is an important trend.

Open Design: Requirements and Domains

Current discussions of open design often refer to two related developments: open production and open design. Design(ing) with reference to the ongoing revolution that is triggered by the ubiquitous availability of digital design and production tools and facilities and that reverses the distribution of design disciplines. It portrays design as an open discipline, in which designs are shared and innovation of a large diversity of products is a collaborative and world spanning process.1 Neither happens by itself and each requires very specific conditions. Analyzing those general requirements will make it possible to achieve a more precise indication of what preconditions would be needed to facilitate open design for government.

DIY DIY is a good example of how open design gets started. To really take off, do-it-yourself production requires access to appropriate materials, tools and techniques to empower enthusiastic amateurs. For instance, DIY projects around the house require a power drill, easily available wood and fastening techniques that unskilled workers can use. This is how amateurs start designing and making things in any field; every professional started somewhere.In the same way, open design emerges in parallel with the availability of user-friendly and accessible information, methods, concepts, values and tools that allow non-professionals to create their designs. Homebrew electronics materials are available in electronics stores, and the corresponding plans can be obtained from electronics magazines or websites. When all these resources are available, more people may be encouraged and empowered to create their own designs.

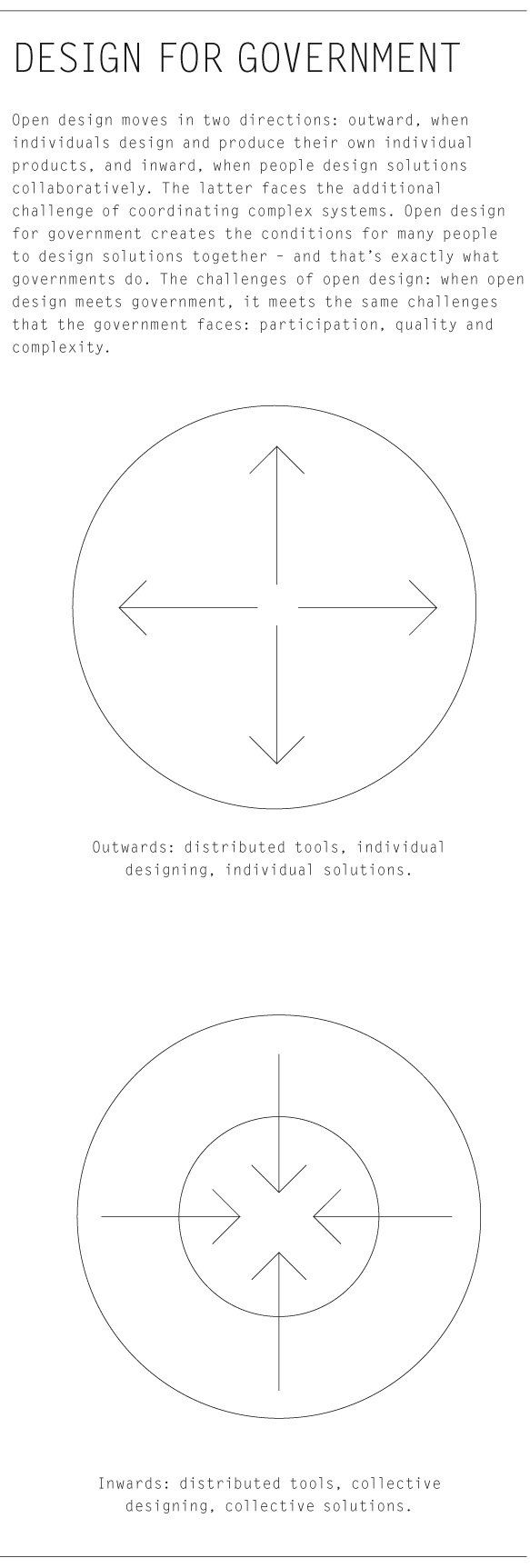

Both DIY production and open design empower the user by putting professional tools in the hands of the masses. Those tools are usually available on different levels. At the simplest level, professional solutions are provided as easy-to-use templates TEMPLATE CULTURE that users can re-use and apply without significant modification. At the intermediate level, tools are available as design templates or generative code that users can modify to create their own designs. BLUEPRINTS At the highest level, skilled amateurs may access and use advanced design tools used by professionals. When open design for government becomes a reality, it will by necessity consist of a variety of ready-to-use solutions, design templates and advanced tools. Open design should be distinguished from other recent design developments in which users have been more intimately involved in the design process, such as participatory design, co-design or social innovation. In open design, many users are able to design on their own. They are not users involved in a design processes that is initiated and run by professional designers. Open design moves in two directions: outward, when individuals design and produce their own individual products, and inward, when people design solutions collaboratively. The latter faces the additional challenge of coordinating complex systems. Open design for government creates the conditions for many people to design solutions together – and that’s exactly what governments do.

Both DIY production and open design empower the user by putting professional tools in the hands of the masses.

Open design for government may lead to different outcomes than are currently being achieved. These outcomes may include harvesting novel ideas from a larger audience, such as in crowdsourcing; improving the quality of a design; promoting participation and loyalty; or facilitating the creation or composition of actual services. Open design may be used for all or any of these, but will have to be adapted to the desired outcome. There are two roles that open design could fulfil in the private sector. First, it could serve the government in its interactions with the people, as a civic resource that gives citizens the ability to take part in the processes of governing. Second, it could serve the government internally to support and contribute to existing government processes supporting government agendas. Again, it could be used in both directions, inward and outward, but the way open design is used would have to be adapted to the desired outcome. The tools for open design themselves are not affected either way, but supporting a pre-existing agenda means obeying pre-existing procedural constraints, which means that open design is not solely reserved for citizens.

When Open Design Meets Government

When open design meets government, design must adapt to the constraints of government in order for the two to interact. In the same way that architects or industrial designers have a basic understanding of building materials, the forces of physics, and the requirements of production, design in the public sector is subject to its own specific constraints. What would open designers need to operate in a government context?

Open design and government might have been made for each other. After all, doesn’t the government work for all of us, and wouldn’t it be much better if we all contributed? In some sense, democracy at large might be seen as a form of ‘design’ where society is run ‘by the people, for the people’: all of the people are involved in designing better futures for each other. However, the structure of the democratic process as it stands now (whether representative or direct) hardly involves citizens in the process of designing new solutions. MASS CUSTOMIZATION The government seems to have its own requirements. So how could the characteristics of open design fit those requirements?

Open design for government will follow government activities. The government is involved in setting policies and providing services in such domains as economics, infrastructure and urban design, welfare and healthcare, culture, education and public safety. These are the subjects of government, and open design for government will have to produce useful solutions in those areas in order to be successful.

The government’s agenda mirrors society’s needs. Running a country or a city involves a finite number of activities; one might assume that open design would focus specifically on those activities. It can be compared to having a family, which also involves making a finite number of decisions in consensus: we really only need to sit down together a few times a year to deliberate such matters as buying an expensive household appliance, deciding where to go on holiday, choosing where to move or what school would be best for our children. While the process of open design may involve more people in the discussion, it will not increase the number of issues on the agenda, nor make dramatic changes to its structure.

Public administration works for the public good. Accordingly, open design for government will have to balance the wants and needs of many different citizens while dealing with power, politics and the manufacture of consent. That is why open design does not mean designing individual solutions for individual cases; rather, the process will have to take into account the balance of power between different stakeholders. One of the important elements in that process is fair representation: open design for government cannot be a process taken on solely by the strong and able; it must also involve the weak and underrepresented. SOCIAL DESIGN

Open design for government needs to support a deep and empathic sense of the needs of ‘users’. The best solutions never consider such concepts as ‘society’, ‘citizens’ or ‘the public’ to be a generic class. One neighbourhood is not the next, one side of town is not identical to the other, and one city does not face precisely the same challenges as another. The same holds true from one generation to the next, and no group in society can be considered a carbon copy of another. Either the open participants, or the process in which they are involved, needs to have the ability to recognize and honour these distinctive qualities and let them ring through in the solutions that are created through open design. In order for open design for government to be effective, it has to be sensitive to the rhythm of government. Policy and development processes have their own dynamic and may take many years to synchronize. To achieve maximum effect, any contribution needs to play its role at the right time in the policy cycle or development process. It will be a major challenge to integrate a complex process of open design, with its own dynamics, without disrupting the necessary tempo and quality of decision-making.

Participation

Open design implicitly assumes that many people will participate once tools and materials become available. However, participation is more complex than that. Participation in today’s political process is a challenge in itself, but participation in online activities is also uneven. On large-scale, multi-user communities and online media sharing sites, user contributions are characterized by participation inequality. Only 0.16% of all YouTube users actually contribute video content; approximately 0.12% of Flickr users contribute their own photos. It’s called the 1% law: only 1% of users contribute, while 9% post comments, and 90% are silent observers.

Doesn’t the government work for all of us, and wouldn’t it be much better if we all contributed?

What’s more, the online communities on those sites are not representative of average web users; actual participation is probably lower if the subset is extended to include all websites on the internet. In itself, the 1% law does not have to be a disadvantage. It closely resembles the state of political participation: only 3% of the Dutch population is actively involved in a political organization; of those, about 30% are active in local politics: about 1% of the population. Early findings on the reality of online political participation show that it tends to be biased, and, just as in real life, the active participants are always the same group of people. Preliminary research on e-petitions for the German Parliament shows this. The online audience is a different group from the people who participated in real life (in this case younger), but online political participants seem to belong to a separate group anyway: highly educated white males.

In open source software development, participation is a major challenge. Projects have a hard time finding enough people who are sufficiently qualified and motivated, and an even harder time keeping those people involved. The current successful examples, such as Linux and Apache, draw their contributors from the 1.5 billion users on the global internet – and only about 1600 programmers among those 1.5 billion users are actual contributors. Scaled down to the level of small cities or neighbourhoods, that level of participation presents a major challenge. Although there are more than 120 million blogs on the internet, it is hard or even impossible to find one good blogger at the level of a single neighbourhood. There is simply too little news content and too few people able and willing to write daily or weekly posts. In the Netherlands, the number of contributors to the Dutch version of Wikipedia is too small to maintain good-quality content. Open design for government may be a good idea, but finding enough people to sustain it will be a challenge.

To really participate in a process of open design for government, participants would at least need access to information on aspects like the financial, regulatory and political consequences of their design effort.

Another widespread assumption is that there is a correlation between civic participation and the democratic quality of society. A related assumption is that finding ways to increase online participation will, in turn, contribute to the democratic quality of society. Research does not support that assumption; rather, it shows that the relationship between participation and democratic quality may be more complex.

Quality

One of the challenges of open design for government is quality. Decision-making at a government level is not about individual and small-scale projects, nor is it about short-term, localized projects. Any contributions to the process would have to create the kind of quality that supports large-scale, long-term projects, answering to regulatory, financial and political constraints. Of course such an argument may be focusing too much on the design outcome: the real result of open design for government might be a greater sense of participation, transparency and increased loyalty.

Involving more people does not create better design, most of which comes from individual designers or small teams. In fact, involving more people may be detrimental to the quality of the result. Of course a larger group may produce more unexpected and useful ideas – that is one of the ways that crowdsourcing produces results. CROWDSOURCING However, turning ideas into a good design requires a completely different process. An illustration may be seen in online petitioning. First results show that e-petitions often fail to contribute serious new policy ideas, though they may increase the people’s feeling of participation and transparency.

Good design requires experience and knowledge of many different aspects of materials, production, marketing and user needs. Design for government is its own domain requiring its own skills. For social innovation, where designers operate in a social context, professional designers estimate that about 5% of their colleagues possess the necessary skills to deal with new and different complexities. Open design for government invites untrained and unskilled participants; the open design process must empower them in a way that compensates for their lack of experience. In open design for government, projects may be active in a wide variety of domains and bring complex challenges on different levels. Open design is simple where challenges and solutions are straightforward and the aim of the process is participation. But when real complexity comes into play, creating the right prerequisites for open design becomes more of a challenge – it will require more extensive information, better tools, more refined methods and deeper shared values.

The Ecology: Information, Tools, Methods and Values

Open design relies on participants who have been empowered with the right information, the right tools, fitting methods and shared values. When done well, these create a constructive balance between the complexity of the design task and the abilities and motivation of the prospective participants. To really participate in a process of open design for government, participants would at least need access to information on aspects like the financial, regulatory and political consequences of their design effort. Then they would need tools to work with that information: visualize it, analyse it, integrate it. They would need methods to support the design process and the manufacture of consent. All of this would be active within a framework of values and concepts that is needed to design appropriate solutions.

New digital tools allow users to create mashups that show the policies and regulations currently in effect on every piece of land and property.

The field of urban design shows the complexity and the power of such an ecology of information, tools and methods. In that field, basic information is becoming available now that datasets of geographic and policy information are open to citizens. This trend is apparent in the DataGov projects in several countries, including the US, UK, Australia and the Netherlands. New digital tools allow users to create mashups that show the policies and regulations currently in effect on every piece of land and property.

After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Louisiana was in urgent need of immediate community redevelopment, which had to be implemented far more quickly than usual. The Louisiana Speaks Regional Plan was a key part of the response. One of the design tools used in the project was the Louisiana Speaks Pattern Book, a resource used to inspire and empower all those rebuilding their communities. It contained an extensive analysis of Louisianan quality in buildings, communities and regions and provided design patterns for new houses and communities, formulated as easy-to-understand examples with the aim of inspiring better, higher-quality projects. The design patterns incorporated the complexity of historical analysis, the qualities specific to the region and the possible modern interpretations in such a way that it was easier for designers to create quick solutions while retaining good quality.

These efforts were based on another generative model, which aims to bring about a ‘21st-century correction’ of the American urban landscape. Called Smartcode, it outlines the best physical attributes of regions, communities and individual buildings and specifically embodies the views of the New Urbanism movement. It addresses all levels of design, from regional planning and the shape of communities down to individual buildings. Smartcode also outlines a design method in which local citizens are actively involved in calibrating the general design code for use in local circumstances. All this shows that, in urban planning, the general trend is increasingly facilitating the requirements for open design. As basic information becomes available, various tools are developed to use the data, followed by a design method that supports active involvement by citizens; finally, the code clearly describes its value systems. Of course, we may want to influence the trends to ensure that they suit the needs of a real open design for government – but the basic elements of the ‘open ecology’ are being developed.

This is just one example; there are many more, but it illustrates the necessary ‘ecology’ in which different components (information, tools, methods and values) may be necessary to support open design. The necessary support framework may be more readily apparent in urban planning, since it is already a design-based domain. When open design meets government, we should see a similar development in other domains like healthcare, welfare, public safety, economics and education. Creating the same ecology for policymaking in healthcare or public safety will require further development.

Fostering Open Design for Government

Open design is in its early stages and open design for government is a promise at best. What if we not only described the possible preconditions needed to facilitate open design for government, but also developed an agenda to stimulate it? Although some projects embrace new ways of working, such as crowdsourcing to involve citizens, that is far from open design for government. A much clearer practical agenda may help to harmonize relevant developments, creating synergy and better quality.

An agenda for development would require an investment on four fronts: further developing the core concept, outlining its possible implementations, identifying their components and stimulate experience in different projects. We need to ask ourselves what we really mean by ‘open design for government’, what it could be, what it should be and what it needs. Only a more operational view can provide the basis for a practical development agenda. Scientific studies are not the first priority; there is nothing to research yet. What is needed is a design effort to outline what open design for government might actually look like. We need scenarios, concept studies and small projects to refine possibilities and parameters. Such a clearer understanding of what open design actually means would allow us to gauge the current trends (such as open government data, new tools for visualization, new developments in design) and to determine whether they possess the right qualities to support a truly open design process.

We will see open design being used in government, partly because design is becoming more important, and partly because the tools and methods necessary for open design will become more readily available. Open design may serve a range of aims, from creating a sense of participation and harvesting new solutions, to genuinely inspiring better solutions for government challenges. However, in order to realize the potential this presents, we will need to make the move from dreams to reality, despite the serious challenges that arise in considering open design for government. As practical concepts are developed further, creating synergy between new and current developments may provide the parameters needed to support open design for government. Whether all of this will lead to higher-quality design for government will depend on the quality of the tools, methods and values that we come up with. Perhaps it is time to make use of the open design process in establishing open design for government.